Crowdsourced environment data gets a home on Louisville Data Commons

Academic researchers and city officials in Louisville, Kentucky, are hoping a new open-data repository aimed at tracking public health and environmental data will give residents a better understanding of their city’s air, water and wildlife.

The “Louisville Data Commons” repository, announced by the University of Louisville on Tuesday, is an open-data website that will incorporate data contributions from residents and researchers to keep track of the city’s environmental and health-related measurements. The community-gathered data will be available for research for a minimum of one year, according to the site, while some larger, frequently updated data sets will be available indefinitely.

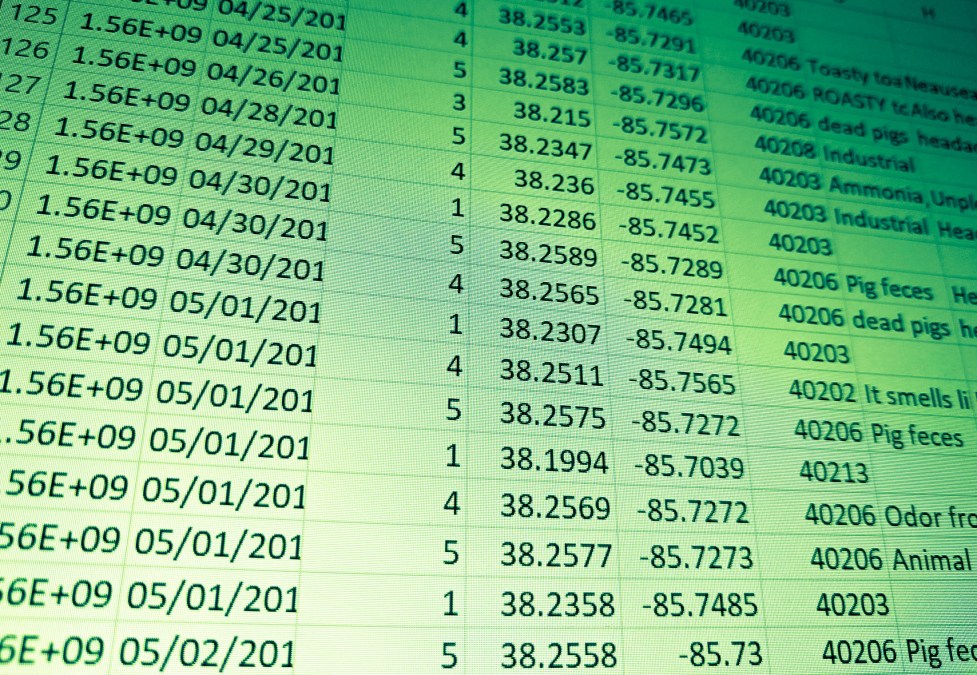

Eight such data sets are available today, including a community cleanliness index, pollen count, tree health and odor reports. Once validated, other data sets will are also to be posted to the site, including those on data-science projects, experiments about Louisville, sensor projects, air and water quality, weather, and non-profit groups.

“Louisville Data Commons is a great example of educational institutions, community partners and Louisville Metro Government working together to create a new tool to help local innovators change lives for the better,” Louisville Mayor Greg Fischer said in a press release.

The city also hosts an open-data website stocked with government-collected data sets, but it did not have a space for residents or researchers to contribute data themselves. The Louisville Data Commons will be that space, said Ted Smith, director of the Center for Healthy Air, Water and Soil inside the University of Louisville Envirome Institute, which is hosting the website.

A seven-member council will manage the site, which runs on CKAN, an open-source data-management platform. The first council includes Smith, Grace Simrall, the city’s chief of civic innovation and technology, along with students, academic researchers and other community stakeholders.

To contribute data, residents simply email their data sets along with a short explanation to the website. Before it’s posted, at least two members of the council will review it for credibility. According to the city, community members expressed concern over whether some of the crowdsourced data on the site had been properly verified. One such source, an app called Smell MyCity, which allows residents to report foul odors, is manually verified by the council, just like the rest of the data.

“The growth of citizen science and the excitement around low-cost sensors has highlighted the great need to have a place where information gathered by our community, in our community, about our community can be made available to our whole community and governed by our community,” Smith said in a press release.