These app makers are trying to shatter Facebook’s echo chamber

With 2.3 billion users, Facebook has the potential to serve as the preeminent platform for honing ideas, an engine that could fuel the discourse propping up democratic governments around the globe and ultimately deliver the world’s inhabitants to a higher standard of living. But more frequently, the world’s most popular social media website serves as an echo chamber whose reverberations have little bearing outside its digital walls.

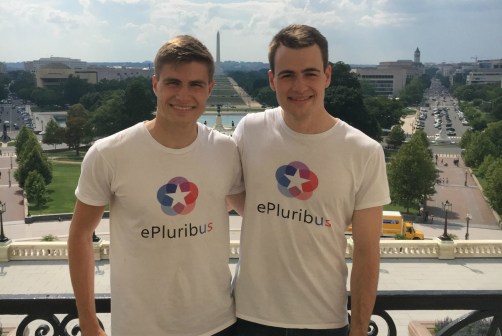

Aidan and Liam McCarty, the founders of a technology company called ePluribus, want to change the role that social media plays in society by creating a tighter link between the discussions people are already having online and the channels of communication leading to their elected representatives. In September, the brothers from Wisconsin closed a $865,000 round of seed funding from investors from their home state and Silicon Valley, and the browser extension they’ve created has recently entered beta, readying for a public launch.

The effort to loop public opinion into political discussion aligns closely with goals of top technology officials at the state and local levels. Inside the offices of many state chief information officers, digital technology is heralded chiefly as a means to connect with the needs and concerns of residents whose historical relationships with government may have been sparse or absent altogether. The McCartys founded their company with the idea of modernizing discourse in parallel with government’s technological transformation.

The brothers have a lot of big ideas of how to change how people behave online, but they’re starting small.

“The vision here for the very short term is that we want to fix politics on Facebook,” Aidan McCarty said. “I had noticed with my friends, and also with myself, I wasn’t engaging with political issues so much on social media or publicly because it was such a hassle. You had to either go way out of your way to actually reach out to the representative and wait a long time to get any sort of response and it didn’t feel like you had any connection. Or you had to join the pundits and the extremists on social media who were just kind of shouting into the void. And none of those seemed like a good option.”

Users who install the ePluribus browser extension are asked to enter their names, emails and physical addresses. From there, they will see a new form appear beneath each news story on Facebook, Twitter or news website that allows them to select one or more of their representatives and send them a message. The app also generates an image that shows the sent message and who the user shared it with, so — the McCartys hope — people will share the image, encouraging others to follow suit.

“It’s kind of like the equivalent of an ‘I voted’ sticker online for civic engagement,” Liam said.

Meeting people where they are is what sets ePluribus apart amid a sea of projects with similar goals. Few have succeeded in gaining a significant user base. Brigade, an issues-themed social network backed by former Facebook executive Sean Parker, remains relatively unknown with an estimated 200,000 users in 2016.

The McCarty brothers say their tool could also help bring a level of trust back to online comments that shape political discussions and policy. The Pew Research Center uncovered that 94 percent of the 22 million comments filed with the Federal Communications Commission amid last year’s net neutrality proceedings were duplicates. Rather than calling on people to send a form letter or to simply sign a petition, the McCarty brothers want people to share with their government the unique comments they’re already taking the time to think through and write out.

“The typical dynamic of democracy is strength in numbers and if you make a lot of noise, typically their ears perk up,” Liam said. “I think people kind of know that, but it’s hard to know how to make that noise. So far, people have been resorting to methods that really aren’t that effective. It might be a hashtag or something on Twitter. That might get reps’ attention, but it doesn’t tell them much.”

Ahead of the tool’s launch, the McCarty brothers are aware of the challenge they’re up against. Educating people that the tool exists could prove a major barrier to success, which is why they’re piggybacking on the existing audiences of Twitter and Facebook to reach critical mass. But if the project succeeds, Liam said, it will ultimately be because it’s is meeting a latent need people have today.

“A lot of frustration with politics is not directed anywhere, because people don’t know what the outlet is,” Liam said.

Aidan said people feel “ostracized” by the whole exercise of online political discussion, but that this technology can bring them back in.

“We’re not trying to change the democratic process,” Aidan said. “We’re just trying to help people have a voice.”