Why federal LGBTQI+ data collection should concern state, local officials

In January, the Biden-Harris administration rolled out its Federal Evidence Agenda on LGBTQI+ Equity, which directed federal agencies to begin collecting sexual orientation and gender identity — or SOGI — data in census surveys and on federal forms like benefits applications.

The administration says this data’s being collected to “advance equity for LGBTQI+ Americans” by learning more about them, but this brings up questions about what state and local governments might do with that data if they get it.

In a political landscape where several states, including Florida, Tennessee and Texas, have proposed legislation or passed laws banning drag performances, gender-affirming care and talking about LGBTQI+ topics in schools, sharing or publishing that data presents uncertainty about the safety of those in the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and intersex community.

Several data and privacy experts told StateScoop they’re concerned about the potential applications and sharing of SOGI data — and what agencies could be doing to prepare for the arrival of that information.

Lack of guidance

The LGBTQI+ community has long been subject to discrimination, and it’s the only minority group in the U.S. that has been legally targeted through differential privacy protections. Though the Constitution’s Fourth Amendment preserves an individual’s “reasonable expectation of privacy,” LGBTQI+ individuals were singled out through laws criminalizing sodomy. That was true until the 2003 Supreme Court ruling Lawrence v. Texas, which found that the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment protected consensual, private sex acts regardless of the participants’ genders.

Privacy — at least within a queer person’s home or personal life — seemed to be protected by this 2003 ruling. But in recent years — and even as an intergovernmental push for increasing privacy measures unfolds on the state level — the right to privacy for LGBTQI+ Americans is facing new attacks and in a new way.

For transgender and non-binary individuals, who make up the part of the LGBTQI+ community most directly targeted in state legislatures as of late, the right to privacy in health care is core to the conservative push to restrict gender-affirming care. Of the record-breaking 338 anti-LGBTQI+ bills advancing in state legislatures as of March 15, 87 target trans health care, even more seek to regulate gender identity and more are being introduced every week.

The White House has warned of a “dangerous” onslaught of Republican state lawmakers introducing bills, leading some researchers to worry about the federal government creating a data trove on the LGBTQI+ community. The potential secondary uses of this data, should states get ahold of it, isn’t just a hypothetical — some Republican politicians are already expressing interest in the data.

Florida has become a stronghold of anti-LGBTQI+ legislation with last year’s “Don’t Say Gay” bill and this year’s renewed efforts to restrict gender-affirming care. And the state’s interest in LGBTQI+ data comes with questions of intent. In January, Gov. Ron DeSantis requested the medical data of students attending the state’s public universities who sought gender-affirming care. A state spokesperson told Insider the reason for the data request was for “understanding the amount of public funding that is going toward such nonacademic pursuits to best assess how to get our colleges and universities refocused on education and truth.”

‘Not in the report’

While the White House’s agenda says collecting this information is for learning about challenges facing the LGBTQI+ community and rectifying a historical lack of data, the agenda does not concretely lay out privacy protections for the sharing of this data between federal agencies, or from those agencies down to state and local entities.

Instead, the White House vaguely advises the federal agencies that would be collecting this data, such as the U.S. Census Bureau, to avoid sharing the data if the agency “determines that there are risks to the safety, health or well-being of LGBTQIA people with the sharing of information.” This leaves each agency responsible for conducting its own risk assessments. But with data privacy and disclosure laws varying vastly at the state and local level, what might count as a risk also varies.

Shea Swauger, a senior researcher for data sharing and ethics at the Washington think tank Future of Privacy Forum, said that because the U.S. has yet to pass comprehensive privacy legislation at the federal level, the agenda’s lack of guidance on operationalizing the data collection of LGBTQI+ populations and sharing the results with non-agency, state, tribal and local partners in addition to researchers, is bothersome.

“It doesn’t tell you how to identify risk, and it doesn’t say, ‘Just don’t share it with bad people,’” Swauger told StateScoop. “And that’s where I think that not just the queer community, but lots of different communities have some ways to operationalize that and some recommendations around like, how do you do statistics? How do you collect this kind of information? How do you store it? That is not in the report.”

Though risk guidelines could help standardize the approach to collection and sharing across agencies, they might not hold water in a year, six months or even a month from now when the next piece of anti-LGBTQ legislation is introduced.

“And I think in terms of harm, it’s hard to say. I mean, I live in Texas, and it’s impossible to know what the state is going to do next year when it comes to how they treat LGBTQ people. So, I think it’s hard to know exactly what the harms could be,” said Katya Abazajian, an open government advocate and researcher at the Beeck Center for Social Impact and Innovation at Georgetown University.

Os Keyes, a researcher and doctoral candidate at the University of Washington, said this uncertainty and the varied state and local protections against discrimination could make the federal agenda counterproductive. Keyes said the harms resulting from discrimination, even with something as seemingly innocuous as filling out a form or survey, aren’t accounted for in the agenda.

“Filling out these forms accurately puts people at risk — risk that seemed to not be really dealt with in this report,” Keyes said. “But this question of how data is collected and whose hands does it go through to get to the federal government when it’s not aggregated, when it’s got someone’s name on it. Maybe someone’s employee ID, maybe someone’s Social Security number — I don’t see that really addressed in the report. And to me, that is somewhere between deeply frustrating and entirely unexpected.”

Reidentification

Even if state and local agencies can keep data on sexual orientation and gender identity disentangled from identifying variables, the potential for harm is not eliminated.

One outcome of this data collection is the possibility of reidentification. As several researchers noted, the smaller a sample size becomes and the more demographic cross-sections evaluated simultaneously, the more likely it is that this data can unintentionally reveal someone’s identity.

Researchers said reidentification is even more probable for transgender folks because of how small the group is. A recent Gallup poll showed that as of last year, transgender individuals make up only about 8.8% of the LGBTQI+ community, and 0.6% of the U.S. population.

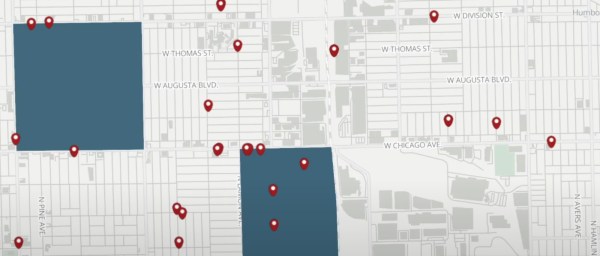

Swauger compared the small number of Black and disabled transgender women in a rural town to the number of cisgendered, heterosexual white men. Cross-referencing ZIP codes with transgender figures in the data, for example, might allow an analyst or lawmaker to identify someone.

“[Data points] work against each other — you want privacy for them, and you want to be able to accurately account for the experiences of having multiple marginalized identities and provide them all the more support because of it. But you are creating a potential target on the back for either the state that they’re in, or the next federal administration,” Swauger said.

Rebecca Williams, a data governance program manager at the American Civil Liberties Union, said the next federal administration’s disposition towards the LGBTQI+ community is also something to be anticipating about when creating the SOGI data trove.

“You don’t have to be that creative to think about if [the administration] changes hands,” Williams said.

She pointed to past examples of data being used to identify and persecute populations: China used data gleaned from mass surveillance systems to detain Uighurs, and government-issued ID cards in Rwanda used “ethnic group” identifiers that allowed militias to carry out genocide against the Tutsi people.

Williams said that while genocide might not be happening in the U.S., the dehumanizing rhetoric that historically precedes it is. Earlier this month, while on the stage at the Conservative Political Action Conference, Michael Knowles, a host at the conservative news network The Daily Wire, said, “Transgenderism needs to be eradicated from public life entirely — the whole preposterous ideology at every level.”

Existing practice does not make perfect

Milda Aksamitauskas, a fellow at the Beeck Center’s State Chief Data Officers Network, said she’s not concerned about the data being shared inappropriately.

Aksamitauskas — who spent 20 years in Wisconsin state government, including at the health department and as the first chief data officer at the Department of Justice — said there are already federal mechanisms in place that would limit transmission of SOGI data.

State agencies administering these programs, such as Medicaid — which might begin collecting SOGI data via applications — are required to transmit some personal data to the federal government in exchange for funding. But state agencies can only analyze that data for in-house purposes, and there are restrictions on sharing it, Aksamitauskas said.

“You cannot just be transmitting that to everyone who asks about it. Like, that does not happen. Data is not shared that way,” she said. “It’s still pretty much siloed in each system that collects the information.”

But even if state and local agencies are not sharing SOGI data with researchers or private groups, that data can still be accessed after it reaches federal agencies like the Census Bureau. According to the agenda, the Census Bureau will be one of the spearheading agencies engaged in this data collection, and its American Community Survey, the largest federal demographic survey, which determines how more than $675 billion in federal and state funds are distributed each year, is named as one of the potential data sources.

While several researchers noted that there are protections built into census practices that anonymize data, even just making this data publicly available — as federal agencies do with other demographic data — presents the risks of reidentification and repurposing.

For example, the U.S. Bureau of the Census State Data Center Program, a national network of state data centers, is tasked with making demographic data accessible to state, regional, local and tribal governments and non-governmental data users. Many policymakers use the network’s demographic data to inform their decisions.

Monica Cruz, the state data center lead at the Texas Demographic Center at the University of Texas, San Antonio, which is part of the Census Bureau’s SDC program, said when state lawmakers request granular demographic data to inform policy decisions, such as the number of Texans who are eligible for Medicaid but aren’t yet enrolled, TDC’s job is to translate the raw data into information that laypeople can understand. She said TDC doesn’t conduct risk assessments on the potential harms resulting from data sharing.

“Basically, everything that we get is really open to the public. It’s census data that’s accessible to anybody. So it’s just that sometimes, staff may not know how to use some of the tools that the Census Bureau has to access that data, or don’t have the time,” Cruz said.

But outside of demographic centers, states and their lawmakers possessing SOGI data can also be concerning because most state privacy frameworks don’t include specific protections for LGBTQI+ folks. Even in California, one of the few states with a privacy law on the books — the California Consumer Protection Act — there is still risk to the LGBTQI+ community.

Chris Wood, the executive director and co-founder of the think tank LGBT Tech, said there’s a loophole in the CCPA for protecting the individual privacy rights of LGBTQI+ folks. Wood said the CCPA affords privacy only to households, not individuals. Wood said an LGBTQI+ minor living in an unsupportive household could be put at risk by the data if their parent or caregiver were to get ahold of it.

How to mitigate risk

Several researchers told StateScoop there are steps the federal government and collecting agencies can take to mitigate risk to the LGBTQI+ community. One involves ensuring that the need for the data is outweighed by the potential dangers of its collection and publication.

“So if the question is posed, ‘What question are we trying to answer with the data?’ Let’s answer that question and do it in a way that reduces the amount of data that we need to be sending,” Wood said. “I say that because the federal government should be holding themselves to the same level of accountability that they are currently trying to hold big tech companies to.”

The agenda does lay out purposes of the data directly, such as securing civil rights in areas such as housing, health care, education, incarceration, employment, residential care, social services, lending and other financial services. Swauger, at the Future of Privacy Forum, said these goals might make federal SOGI data collection worth it, but that encouraging data disaggregation and collection at “the smallest geographies possible” could result in a catch-22.

“If we do it at an aggregate level, to where it can’t be traced back to individuals, you can get a bad compromise of some additional information and services potentially to those communities, but not actually outing them,” Swauger said. “The cons are that the less detailed the data, the less effective some of the services and interventions can be.”

Keyes, at the University of Washington, suggested that the Biden administration consider assigning data collection and management to a nonprofit, such as the Williams Institute, which is already performing data analysis on the LGBTQI+ community at the state level and making it available on a public dashboard.

“We have a load of groups who aren’t subjected to all of these constraints and all of these whims,” Keyes said. “We have community groups, we have rights organizations, so on and so forth. If they really want to collect this data in a way that provides protection, make that the job of organizations who aren’t subject to the same rules and whims and so on and so forth as the federal government.”

Williams, of the ACLU, said state and federal agencies can reduce risk by making secondary uses of the data illegal. She said governments could also just not collect SOGI data at all, though that could have drawbacks. Many transgender people have reported feeling affirmed and protected by having their gender identities accurately reflected on government identification, such as a driver’s license.

If SOGI data collection is to proceed and actually achieve the equity for LGBTQI+ individuals that it aims to, that means talking about these potential harms — even if that could arm some Republican policymakers with new methods or ideas about how to further repress the community. Wood said talking about SOGI data shouldn’t be shied away from.

“It sounds like a doomsday scenario. It sounds like the worst-case scenario, but I think we have to think about it,” he said. “I think spelling that out and really talking about it in a way is so important, because obviously I don’t want to give them ideas but I, most certainly, when we’re talking with companies and legislators, we’re bringing it up. We’re saying, ‘Yeah, this is a worst-case scenario, but the worst-case scenario could happen, and so we need to plan for it and we need to poke holes in it.’”